He turns 25 today. A quarter of a century. From a newborn on life support to an adult on his own. I wrote his story years ago, when the memories were still relatively fresh and new. So much time has passed. So much has changed in our lives. But one true thing will always remain: My love and adoration for this kid of mine who made his way against all the odds. Happy Birthday, Augustus Charles.

Sissy Loves Gus

Living Large in Lex

~ ~ ~

Sweet, quiet Baby Gus — with a cap of auburn curls and an innate flair for the dramatic — made his way into our lives on a bitterly cold February day in 1999. He was a planned c-section. After battling for far too many hours to deliver Sam and eventually vomiting all over my freshly-scrubbed, surgery-prepped, overly-pregnant, non-dilating self, we decided to opt for the c-section without all the preceding drama.

I distinctly remember Dr. Jones proclaiming, “He’s a boy!” as Gus was pulled from my belly.

Chris was distracted by the ability to see my internal organs. “What’s that, Doc?” he asked while gazing at my innards. “What’s that?”

When I glanced at Gus’s sweet face and that mess of wet curls, all I could think about was my two sons growing up together. I was so grateful Sam had a brother. At that instant, I didn’t know Gus well. I loved him with every ounce of my being, but I was so happy for Sam.

While I was in recovery, things took a turn for the worse. Like a play unfolding before our eyes, the ending still a vast unknown, we didn’t didn’t know how bad things were going to get. But our Gus was sick, sick, sick.

“What does that mean?” I kept asking. Before Gus, sick meant a sore throat, a high fever, an ear infection. I couldn’t reconcile Gus’s “sick” with my own limited knowledge of childhood illnesses.

Before he was 24 hours old, before I had a chance to hold or touch him, before his visitors had an opportunity to greet him, Gus was transferred to St. Vincent’s Neonatal Intensive Care Unit in critical condition. Both of his lungs had collapsed, he was intubated, and he was placed in a drug-induced coma. Every minute of his brand new life was touch and go. And I was stuck in a hospital bed an hour away with fresh abdominal stitches and and OB who refused to release me until he felt reasonably certain I wouldn’t end up sick as well.

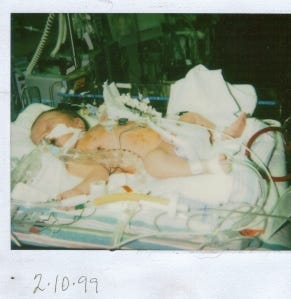

“Where my baby?” Sam asked as he trotted into my empty room. “Where my Baby Gus?” And I held him, and I stroked his blonde head, and I cried tears that wet his upturned, questioning face. Visitors came to see our new addition before the word had spread. Uncomfortable silences filled the room as they arrived armed with blue balloons, blue outfits, blue bibs. I sobbed as Chris called me with updates. He took a Polaroid picture and brought it to me so I wouldn’t be shocked when I saw Gus for the first time. I looked at his still little body, crossed with tubes and wires, spotted with blood, a machine taped to his face, and I knew nothing could prepare me for that particular sight.

Day Two

When I was finally released from the hospital and able to make the drive to Indianapolis nearly 48 hours after Gus’s birth, I was introduced to a world I never even knew existed. Funny how you can meander through life not understanding the gravity of another man’s troubles until they become your own. The NICU was a planet inhabited by devoted professionals, grief-stricken and stunned new parents, and critically ill babies. At seven pounds, Gus dwarfed his preemie neighbors. He looked so robust and healthy, but he resided in the corner of the NICU that was reserved for the sickest of its patients.

I sat in my wheelchair at his bedside watching the ventilator mechanically move his tiny, broken chest, and I willed the air from my own lungs into his. I glanced briefly at the other babies, at the other parents — careful not to invade their private heartbreak, always aware of the tenuous threads that kept these babies feebly tethered to our world.

“Gus is very, very sick,” our angel nurse, Lynn, explained to us softly.

“Will he… die?” I dared to ask one day, choking on the word that had yet to be spoken.

She chose her words carefully.

“Gus is critically ill. But he’s not as sick today as he was the night he came to us. He is still not out of the woods, though. Talk to him, sing to him, love him. Give him something to hold on to.”

And so we did. We talked to him. We sang to him. We recorded a tape that the nurses played for him when we grabbed a few interrupted and restless hours of sleep in the waiting room. On that tape, I sang softly about The Things We’ve Handed Down. And I cried as I recorded, “Don’t know why you chose us. Were you watching from above? Is there someone there who knows us, said we’d give you all our love?” I wondered what Gus heard through the fog and haze of his medication.

Lynn explained the various doses he received through the central line that was stitched into his chest. “This one is for pain. This one is for edema. This one is for infection. This one helps him forget.”

Heartbreaking to think that Gus needed to forget before he even had a chance to remember.

Days in the NICU are measured in minutes, in seconds, in minuscule victories. His PEEP settings improved today. Victory! His oxygen saturation levels dropped. Two steps back. Leaving the NICU for food, for clothes, for Sam was a step into a bright, unfamiliar world. I squinted in the daylight, an animal coming out of hibernation. The noises were too loud, the cars too fast. Conversation was challenging, English seemed an unknown language during those days. I couldn’t produce cohesive thoughts, couldn’t form sentences. I had too many foreign words clogging up my mind: Vecuronium, Versed, pseudomonas pneumonia, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, pulmonary interstitial emphysema. When contemplating these realities, there was little room left in my brain for words such as these: weather, politics, grocery shopping.

Sweet Sam was jostled from home to home, always wrapped in the tender, loving care of our family and friends, but clinging fiercely to me when it was time for us to part again.

“Come home, Mama,” he’d beg. “Please come home.”

And his pleas would tear my heart in two. Half would follow him to his next destination, his next sleepover. The other half stayed with my sick baby. I don’t know which one needed me more during those horrible weeks, but I know there wasn’t enough of me to give them both what they required.

Days turned to weeks, and still Gus struggled. I pumped milk for him in the nursing room and stored it in the communal freezer. Someday he would need it. Someday. Strapped like a cow to the high-powered milking machine, I produced more milk than most of the other mothers combined. Once when I pulled my overflowing tray of bagged and frozen breast milk from the freezer, another mother looked and me and said, “Oh, you’re the one.” And so I was. The milk producer with the overactive mammary glands. The wet nurse with no one to feed.

“You should open your own Milk Bank,” Chris joked with me. “We could pay for these hospital bills with the profits.” Dutifully, I kept pumping, kept freezing. It was the only measurable things I could do for Gus. One day, I fell asleep with the machine turned on, and awoke with nipples stretched to three times their normal size. I laughed at the sight, and then cried at the absurdity of it all. For half an hour, I sat in that nursing room with my disfigured nipples exposed for all who cared to see, and I sobbed with the force of a breaking dam.

Such was life in the NICU.

Our best friends sustained us during those trying times. Brent and Jackie lived within walking distance of the hospital, and they opened their home to us. They sheltered us, fed us, cried with us, cared for us. They got up with us in the middle of the night when the doctors would call and tell us to come in right away — that this night might be Gus’s last. We stumbled in and out of their home, we left their refrigerator door open in our tired stupor, we let them raise and nurture our healthy child while we whispered to and pleaded with our sick one.

“Honey,” Jackie questioned one morning as we clutched our coffee cups, “did you mean to park in the yard?” I looked out the window and saw Chris’s blue truck sitting squarely in their front yard. In the wee hours of the morning, I’d arrived at their home and neglected to take the car out of gear. In the night, it had made its way into the grass and had come to rest by their front door.

“No,” I sighed. “No, I didn’t mean to park in the front yard.” And then I chuckled. But the gesture felt so foreign, so wrong, that I burst into tears instead.

“Shh, shh…,” Jackie whispered, rubbing my back and smoothing my tangled hair. “It’s just grass. It will grow back.” And I knew she was right. This blades of grass that had been crushed by the weight of my husband’s work truck would spring right back to life. And still my baby couldn’t take a breath on his own.

One miraculous day when I stumbled my sleep-deprived self into the NICU after the 7:00 AM shift change, Lynn greeted me in the hand sanitizing room with a playful smile.

“Looks like Gus decided today was a good day to be born.”

When I approached his open-air bed in the sea of tiny incubators, I saw what she meant. There was my boy with his beautiful, soulful eyes wide open, staring in wonderment at his surroundings.

“Hello, little one,” I cried as I gingerly held his tiny hand, battered with needle sticks. “Hello, precious baby boy,” I sobbed. “Welcome to the world. Welcome, Gus. Welcome.”

Lynn explained that Gus had broken through his medication and that as long as his vital signs remained stable, they would let him stay awake.

Perhaps the most gut-wrenching moments of those following days were the times when Gus would cry — silenced by the tube that ran between his vocal cords, yet visibly upset, fat tears rolling down his puffy cheeks. Day after day, Gus’s edema worsened. His little bloated body continued to swell and grow as the doctors battled to find the right combination of drugs to keep his lungs working, to keep his kidneys from failing. Always a balancing act in the NICU, always a game of wait-and-see.

Chris and I learned about pacing, about celebrating the small victories and surviving the inevitable setbacks.

“This is a marathon, not a sprint,” Dr. Tolliver informed us at the beginning. And so we trudged on, thirsty for water, in need of rest, desperately searching for the finish line. And Gus journeyed with us, fighting valiantly for his brand new life, courageously battling to draw an unassisted breath.

Twice, he failed extubation. Twice, we held our own breath as his mechanical support was removed. Twice, we watched his oxygen saturation levels plummet. Twice, we witnessed the doctors painfully inserting another tube into his lungs with heavy sighs and promises of “next time.” At night, I dreamed about him floating carelessly in the darkness of my womb where there were no harsh lights, no painful needle sticks, no mind-numbing medications. I wished him back inside me where I could feed and nurture him with my own body, where I could protect and sustain him.

One night, after returning from vacation, Dr. Andrews came to visit Gus in the NICU.

I cried at the sight of our healer, our beloved family physician. I begged him for information, for answers.

“Is he going to die?” I asked cautiously, stumbling over the very word.

“He’s a very, very sick baby,” he answered with frustration, raising his voice. “Yes, he might die. But you can’t think that way. You have to be strong for him. He can hear you, feel you, draw strength from you. You can’t stand at his bedside crying all the time. This is not about you!”

And as I stifled my sobs and choked back my tears, I wondered how it wasn’t about me. How it wasn’t about Chris. About Sam. Gus was a piece of us, a vital part of our family. Without him, we would not be complete. Without him, we would not be whole.

The following night, we ventured home for an evening alone with Sam. Driving away from the hospital felt like a betrayal. If I looked back, I was sure I’d turn to stone. Sam jabbered in his carseat from St. Vincent’s to our gravel driveway.

“And I had gum at Nanny’s. And I played with Molly. And I read two books…”

We smothered him with kisses, tucked him into his big boy bed, read him as many stories as his sleepy voice could request, and closed his heavy, wooden door. Then I inched down the creaky hallway to the Paddington nursery that was anxiously awaiting its new inhabitant. The air that escaped from behind the door was stale, cold. We had closed the vents to save on our skyrocketing propane costs, and the room now felt like an unused refrigerator. Dead flies lined the freshly painted windowsills. I gathered a sky blue blanket from the crib, and I sat on the cold floor and cried. Hot tears warmed and wet my face until I had nothing left inside. I curled up on the floor, clung tightly to the blanket in my arms, and fell into a fitful sleep. I don’t know how much time passed before Chris gently led me back to our bed. And there we curled up into each other, filling the empty gaps with our arms and legs. Filling the void in our hearts with whatever leftover feelings we could muster.

The phone jarred us out of a restless sleep early the next morning.

“Yes, Doctor?” Chris asked as I snapped instantly awake.

“We’ll be right there.”

“What?” I asked anxiously, dread filling my heart, angry that we’d chosen last night to drive so far away. “What did he say?”

A smile — so foreign, so unfamiliar — tugged at the corners of Chris’s eyes.

“He’s off the vent.”

With frantic excitement, we woke Sam, threw clothes on him and ourselves, loaded up the RoadMaster, and tempted fate with our careless speeding. The morning air was frigid, our happy tears froze instantly on our cheeks.

“We see my baby?” Sam asked over and over. “We see Baby Gus?”

“Yes, Sweetie,” we replied again and again, without hesitation. “We’re going to see Baby Gus.”

“Hooray, Baby Gus!” he shouted from the backseat.

“Hooray, Baby Gus!” we agreed.

Hooray, Baby Gus.

After we’d sterilized our hands and arms and donned our masks and gowns, we raced back to Gus’s bedside. And there, sitting in the ever-present rocking chair, was Lynn, holding our son.

“Would you like to hold your baby?” she smiled at me. “Come on, Mom, he’s been waiting.”

Lynn arranged his remaining tubes and wires and placed his swaddled body into my arms. After four grueling weeks, after two surgeries and multiple extubation attempts, after a week in contact isolation, after discussions of transferring him to a hospital where he could be treated on a heart/lung bypass machine, after 28 heart-wrenchingly silent days and sleepless nights, I was able to hold my second son for the first time.

His serious, cerulean eyes gazed at me with wonder. Then he squeezed his bruised hands into fists and cried, his elusive voice deep and throaty.

“That’s it, Baby,” I whispered in his ear. “You cry. You cry all you need. You deserve it. There you go. Let it out, Gus. Let it out.” And he wiggled in my arms and fought my touch — unused to being held, to being cradled, to being awake. The harder he struggled, the tighter I clung to him.

“You’re safe,” I cried. “You’re safe. I’m here, Baby. I’ll take care of you.”

All the while, Sam gently touched his brother’s curly hair and whispered, “Hi, Baby Gus. It’s okay, Baby Gus. I’m Sam. It’s okay.”

And that day, we truly knew that it was, indeed, going to be okay.

Later, when the threat of losing Gus was far enough behind us, I asked Dr. Tolliver how close we’d come to saying goodbye.

“Let me put it this way…” our neonatologist said as he carefully considered his words. “Gus walked to the edge of a very tall cliff. And he looked over the side. Had he taken another step, there was nothing medically that we could have done to keep him from going over. But he’s back now. He’s safe. And he’s all yours. That boy is one hell of a survivor.”

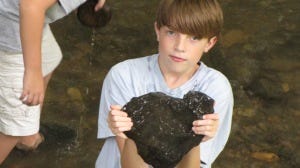

My still water that runs deep. My enigma. My loving, responsible, sensitive, emotional boy. Augustus Charles will always be a bit of a mystery to me, but I think that’s the way he wants it to be. I was never a loner. I don’t understand the loner mentality. Surround me with friends and put me in the center of attention, and I’m a happy girl.

Not so for Gus. He relishes his solitude, languishes in the boisterous chaos of a room full of ten-year-olds. “Leave him alone,” Chris instructs when I ask him if he wants to join a playing group of kids. “He’s happy.” Happy doing his own thing when he wants, where he prefers, and as he pleases. That’s my Gus.

We often describe him as “slipping under our radar.” When we think he’s upstairs in his room, he’s actually wafted past us on his silent trip to the basement. When we think he’s outside playing, we instead find him curled up in a chair with a book. But when I hug him at night in his bed, I know just where he is. Because he clings to me with his skinny, gangly arms, making me think that he might never let go. Wrapped around me tightly, I can hear the staccato beat of his heart and feel the rise and fall of the breath passing in and out of his lungs. The breath we feared he would never take on his own.

He was in such a dark and unknown world his first five weeks of life. Sedated with Versed, we’ll never really know the first impulses that lodged themselves in his baby brain. Did he hear our voices? We’d like to think he did. Did he feel our love and warmth surrounding him? God, I hope so. But what I do believe is that those first five weeks changed Gus, molded him into the emotional, creative, thoughtful boy that he is.

Often a target for adolescents who don’t know what to make of him, I know that someday he’ll be a find man that people will flock to. For companionship, for wisdom, for insight, for life. I’m eager to see what kind of intellectual and spiritual beauty this little cocoon of a boy — quiet, reserved, socially challenged, and easily brought to tears — will someday become.

Sweet Gus.

Love,

Katrina

Wow! What a journey and what a gift of words you found to bring us along, Katrina. You are such a gifted writer, fierce Mama, and warrior in this world. I am grateful and inspired to know and love you. Thank you.

No matter how many times I read it, that story never fails to turn me to mush. Happy Birthday, Gus!