Coming Out

Why Pride matters

I was 46 when I told my mom I was gay. I’d been with my then-husband for 32 years; had been married to him for 25. I had birthed four gorgeous kids—one in college, two in high school, and the baby in his final year of middle school.

My mom rested in her nursing home bed while I held her hand, my stomach twisted in knots, the most terrifying words I’ve ever had to speak muddled in the back of my throat.

“Why?” she asked, confused and distraught, once I finally spoke my truth. “If you’re gay, why did you get married? Why did you have kids?”

As if having a gay mom was the heaviest burden I could saddle my beloved children with.

‘‘I just don’t understand,” she said again and again.

But at that point, I didn’t need her to understand.

I just needed her love.

My mom had always been 1,000% supportive of everything I’d ever participated in: She was in the bleachers at every sporting event, in the front row of the auditorium every time I sang, always available to help me with my babies.

I do remember, though, how Mom used to talk about my Sporty Spice friends when I was in high school.

“You girls are definitely the prettiest, most feminine team out there. Some of the girls you play against are so jock-y and butch. I hope you don’t ever start walking with that manly swagger.” She was joking, but in my mind, her message was clear: I needed to continue to wear makeup and dresses, to present as a lady, to be “pretty.”

Once, when I was in middle school, I tried to tentatively discuss homosexuality with my mom. “No,” was all she said.

I couldn’t really blame her. I grew up in the 70s and 80s when being gay was still criminalized and associated with AIDS and the butt of evening sitcom jokes. My mom grew up in an outwardly racist environment.

Religious indoctrination, homophobia, patriarchy, racism—they are all belief systems that run deep. The things we are taught as undisputed truth in our formative years are difficult to renounce.

Some things are stitched into us so tightly that unraveling them can feel like we’re coming apart at the seams.

When I came out to my sister that same year, we were already in a shaky place in our relationship. We’d disagreed about Mom’s long-term care, about helping Mom and Bob make the best financial decisions to support their later years. I wrote to Carrie because we weren’t speaking much during those volatile days. Her response was simple and expected: “I’ll pray for you.”

It was a gut punch. A throwback to a religion I’d long ago outgrown. An acquiescence to a higher power that I no longer believed in—one that believed instead that who I was was wrong, sinful, in need of salvation.

Carrie came around eventually. We were both making our way back to each other when glioblastoma took her away forever. Life can be an asshole that way.

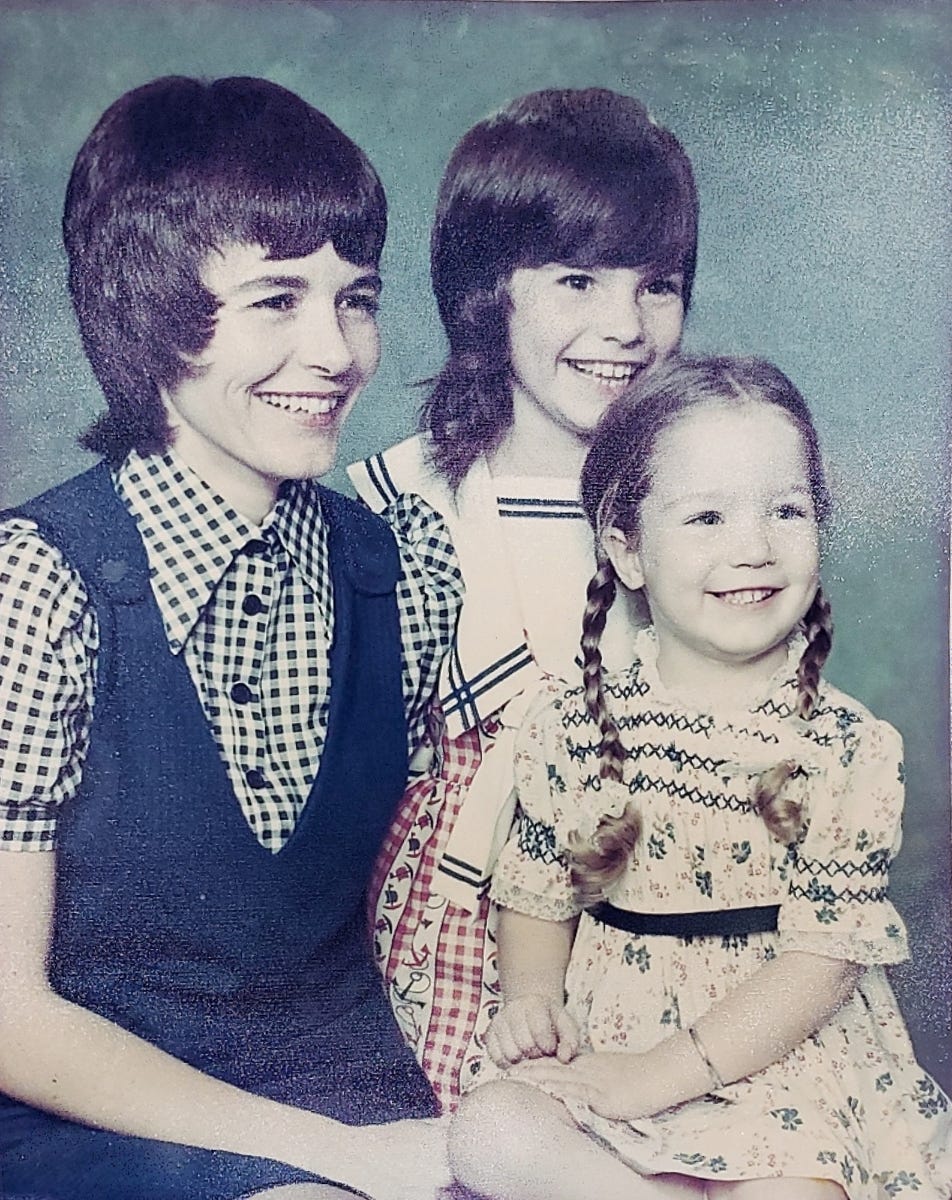

Time matters in these situations. Time to process, time to think. My mom and my sister had most recently known me as a married, heterosexual mother of four. The divorce was shocking enough. But the gay? The gay was earth-shattering. They needed time to see that I was still me. Still their daughter, their sister. They needed time to connect the dots between dodgeball-playing, fort-building, bike-racing little me to rainbow-clad, justice-fighting, animal-rescuing big me. Time to see that our hearts were the same; that it all made sense.

Ruby taught me about connecting those important dots. My kids did, too. When they were little bits, I used to dress my kids alike. With four under the age of five, coordinated clothes made them easier to spot in public places. But truth be told, their cute, colorful clothes made me feel like a better mom—more put-together, more in control, more socially acceptable. But my kids hated those clothes. They wanted to express themselves individually. I was squelching them, and they let me know it. One Christmas, Sam said to me, “This is it, Mom. This is the last time I’m dressing like my siblings for Christmas pictures.” It was a liberation for all of us. If you know my adult kids, you know they are the antithesis of “matching clothes kids.” They couldn’t be more unique individuals if they tried. Thank goodness little Sam reminded me of that early in the game.

When I adopted Ruby, I wanted to open her eyes to the world. I wanted to take her everywhere—on hikes, to dog-friendly restaurants, to parks and parades, on weekend trips. But Ruby just wanted to hide under something. Anything. And if there wasn’t anything to hide under, she wanted to sit in a corner with her nose to the wall.

Ruby was not social. Ruby was never going to be social. Even today, at eight years old, her favorite place to be is under the bed or in her crate in the shower. Ruby knew who she was from the jump. It was me who had to learn, who had to accept that my sweet pup was going to be a different dog than I wanted her to be, that my expectations of her were in direct conflict with who she actually was, and that I would love her just the same. When she comes to me now and sits with me for a very short spell, I love running my hands over her soft-as-silk fur and marveling at all the trauma she’s been brave enough to survive. What a wonder this sweet dog is. What a gift she’s been. What poignant lessons she’s imparted.

My mom, as always, didn’t require much time to adjust her expectations to my reality. She understood that at the core, loving me unconditionally was more important than any internal conflict or discomfort she might have experienced. That was the beauty of my mom. Her love was as big and eternal as the sea.

I do wish, though, that Mom and Carrie had been given more time to know queer, adult me better. She’s a lot like little me and teenage me before I tried to mold myself into what I thought I should be. Today’s me is sassy and opinionated—like little red-headed, breath-holding me. But she’s also tender-hearted, inquisitive, and prone to big feelings. She’s less focused on self and more focused on the state of the world. She wants better things for her kids, her friends’ kids, for everyones’ kids. She wants a kinder, gentler, more equal existence. Material things no longer matter so much to her, although she still loves a good pair of kick-ass shoes. Like most with more decades of life behind her than in front of her, she’s experienced pain and injustice and loss and devastation. But also, joy and celebration and wealth that is measured in friends and family and more love than she has ever deserved.

She wishes she could share a Keoke coffee with her mom and a frozen margarita with her sister and laugh like they all did in their younger years, with tears of happiness spilling down their faces. Because she’s the same person she always was—just a little rounder and a little more queer and a lot more gray-haired.

And the love and acceptance of her family has always sustained her.

How lucky I am.

How lucky I’ve been.

If you are lucky enough to love someone who’s queer, don’t wait too long to hug them, to tell them, to share a Keoke coffee with them.

Life is short, but love is forever.

Happy Pride.

I was never more proud of my parenting when Grace, after realizing she was queer in college, said to me, "Did you know some kids can't tell their parents they're gay? I couldn't believe that!" We are changing the narrative, my friend. Generational trauma ends with us!

Hello beautiful Katrina.

I loved reading every bit of your raw honesty in the relationship with your mother and children. Rebellion and revelation and revolution rings through throughout this entire piece especially your children refusing to dress alike. I love that. Happy pride month every day, I stand with you and have my own stories. 🧡💜💙💚