Listening to him play the violin is one of my greatest joys.

My youngest son, George, began taking lessons when he was ten, back when I homeschooled him for a few months in Mississippi. On his very first day in his new Mississippi school, he’d been punished and made to stand in a corner for not saying, “Yes, Ma’am” to his teacher, even though no one had told him that was the Southern expectation.

He cried so hard when he came home that day, embarrassed in front of his new classmates, and fiercely missing his best friend in Indiana.

“Don’t make me go back,” he begged. “Please don’t make me go back.”

His pain was so big, it just continued to grow until I feared he’d lose himself in it. So, I agreed to teach him at home, and the first thing he wanted to learn was how to play the violin. We lucked into finding an amazing teacher who was Juilliard-trained, and George’s violin performance career was launched.

Fast forward 15 years, and not only does he play the violin, but he’s picked up the guitar, the banjo, the ukulele, and the mandolin as well—all self-taught. Watching his long, lean fingers as he’s playing is like examining a rare piece of art.

So is witnessing his joy.

George has always been interested in doing things with his hands. As a toddler, I’d walk away to throw a load of laundry in the washer or tend to one of his sibling’s skinned knees, and I’d come back to find him happily emptying a shelf, sitting in a pile of books, grinning impishly. It was a game we played again and again—he’d deconstruct my bookshelves, and I’d restock them. It wasn’t my favorite activity, but it gave him such happiness to pull a book off a shelf and throw it on the floor. And sometimes, his de-shelving game would even buy me a minute to eat an apple or fold some clothes.

When he was in elementary school, George became obsessed with LEGOS, building things with his eager and capable hands and his complex imagination. One year for Christmas, he asked for old electronics that he could dismantle because he wanted to figure out how things worked. That year, I shopped at thrift stores for George’s gifts, and he woke with unadulterated excitement on Christmas morning to find an old toaster, a coffee maker, and a vintage boom box under the tree amongst his siblings’ skateboards and scooters and American Girl dolls.

With four kids ranging in age from six to eleven and a spouse who was always at work, in school, or chaperoning an event, I spent most of my time in our Suburban, chauffeuring my kids to and from school, to sports practices and games, to birthday parties, to doctor’s appointments, to play dates, to Target, to music lessons, to theatre rehearsals. Even with a one-activity-per-kid-per-season rule, we were still over-scheduled and always on the go.

There was one day during these frenetic years when I picked the kids up from school and promised them a treat. We didn’t have enough time to go home before Sam’s basketball practice, but there were a few spare minutes to grab ice cream cones from McDonald’s.

We were on a tight schedule, though, or Sam wouldn’t make it to practice.

Once we parked, I quickly began unloading the four kids by moving seats, and helping unclip seat belts. I lifted George out of the car first, and he knew the rule and the routine: Stand right beside the driver’s door until everyone else was out. Then we’d all walk through the parking lot together, Sam and Gus in a pair, and Mary Claire and George holding my hands.

But once all the kids were unloaded, and I tried closing the driver’s door, it just kept bouncing back open. I slammed it again and then slammed it harder, growing confused and frustrated as to why it wouldn’t latch.

“Come on, Mom,” the older kids began whining.

“I don’t know what’s wrong with this door,” I said. “It won’t close! We can’t go inside with the car door open!”

“I’m going to be late,” Sam said, anxiously.

“George, did you touch anything while you were standing here?” I asked, my frustration growing exponentially as our free time ticked away. The kids were getting impatient, their ice cream dreams fading fast, and I couldn’t figure out what was wrong with the damn door.

“I touched this,” George said, pointing to a lever inside the door frame. “I wanted to see how it worked.”

When I looked closer, I could tell that something had locked in place, blocking the door from latching, but I couldn’t figure out how re-enable it.

“Why do you have to touch everything?” I yelled at my four-year-old accusingly, as he stood beside me, his baby blues wide with something resembling fear. “You can’t leave anything alone, and now look what’s happened!”

As soon as those mean, angry words left my mouth, I regretted them, tried to swallow them whole. I was tired and frazzled and frustrated and stressed—my normal, everyday state of being back then—but my overwhelm wasn’t George’s fault.

“Way to go, George,” his siblings began chiding as tears filled my baby boy’s cerulean eyes.

Eventually, I had to call a friend to drive to McDonald’s to help me fix the door, the kids never got their promised ice cream, Sam was beyond late for his basketball practice, and George cried all the way home.

I felt awful, like a screaming banshee and an abject failure and a horrible mother. I had broken a promise to my kids, disrupted our entire evening, and blamed my four-year-old for the whole debacle.

That day haunts me even now. I can still see George’s sweet face as he accepted the blame for the mess, when he was only satisfying his natural curiosity. I mentioned the Ice Cream Incident to him recently—expressing my regret—and although he remembered what had happened, he didn’t recall the day with any special pain or angst.

“You were pretty mad,” he said about what had transpired 18 years prior. “But I remember being more upset that we didn’t get ice cream than I was at your yelling.”

These pockets of time—these little memories that lodge themselves into a Mama’s heart and won’t let go—can eat away at your insides. We can recall all the wonderful things we did for our kids—the birthday parties, the days at the beach, the creek walks, the bike rides, the bedtime stories—but we can also perseverate on those moments when we lost our cool, when we yelled, when we punished, when we accused, when we wished we could turn back time and call a do-over.

The things that stick in my brain, however, rarely match up with the memories that have lodged themselves into my kids’ minds. That can be both a blessing and a curse. I’m happy they’ve forgotten some of my stressed-out tirades. I’m sad they don’t remember some of the fun things I planned with them. But I’m glad I still have those memories, and I will forever keep them tucked away in a quiet place in my heart.

My mom used to lament the fact that I didn’t remember her taking us on kite-flying adventures when we were little.

“You loved it so much,” she used to say. “We’d go to the school yard, and you and Carrie were always so excited. You’d run with your kites for hours. Sometimes we’d take a picnic. I can’t believe you don’t remember.”

There are many things my kids don’t remember, either—even when I thought I was creating core memories for them at the time. But it’s okay as long as they remember me as a loving, kind, attentive, and present parent.

At least most of the time.

And I am so grateful that the day I yelled at four-year-old George for using his hands didn’t stop him from using those hands to pursue what he loves most.

His musical ability is one of his greatest gifts … and he is one of mine.

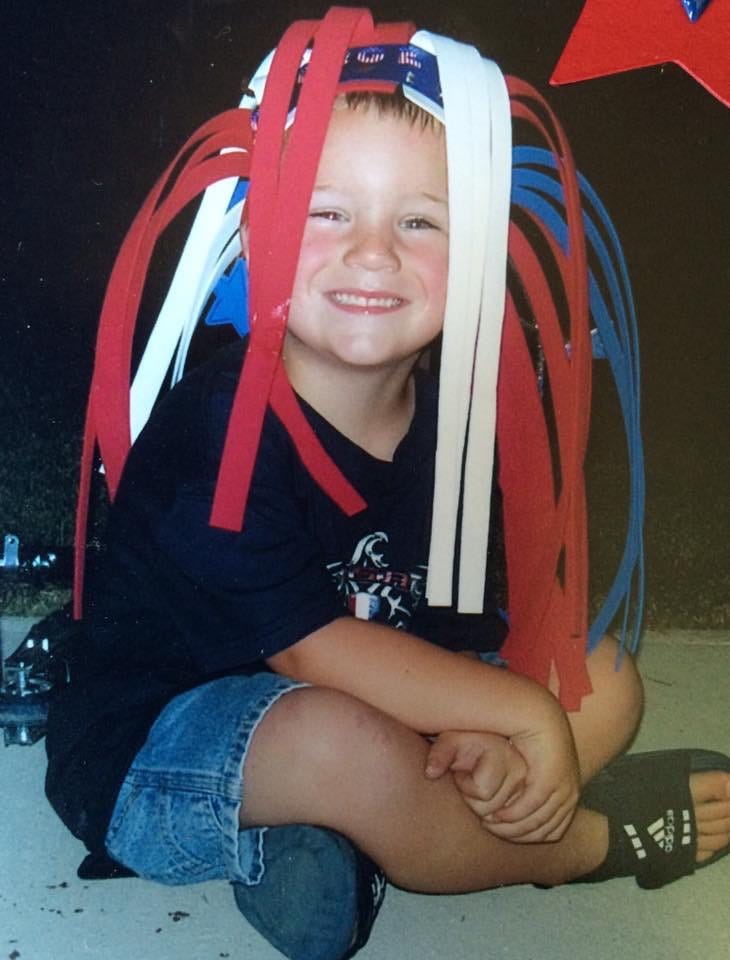

I so enjoyed this, Katrina. Such talent and depths of creativity. Isn't it fascinating those moments of motherhood we wish we could have a "do over" with? How they landed for our children, sometimes very painful to hear, and other moments, they shrug their shoulders as if it was not a "big deal?" Important to have, though, I hear you, an ongoing invitation to put to the side our parent fragility. Terrific pictures too! Such JOY. Xo 💜🪶

What a talented and inquisitive son! It's going to be interesting to see where life takes him.