Nothing Remains the Same

On family, love, and loss

My mom was proposed to more than any human I know. Stunningly beautiful, hilarious, and kind, my mom held court wherever she went. Men stopped her on the street to comment on her looks. Once a man said she was “so radiant, it was like looking directly at the sun.” After that, she’d stand in a sun-brightened spot, strike a pose, and ask, “Do I look radiant here?” Her sense of humor was sharp; her timing, impeccable.

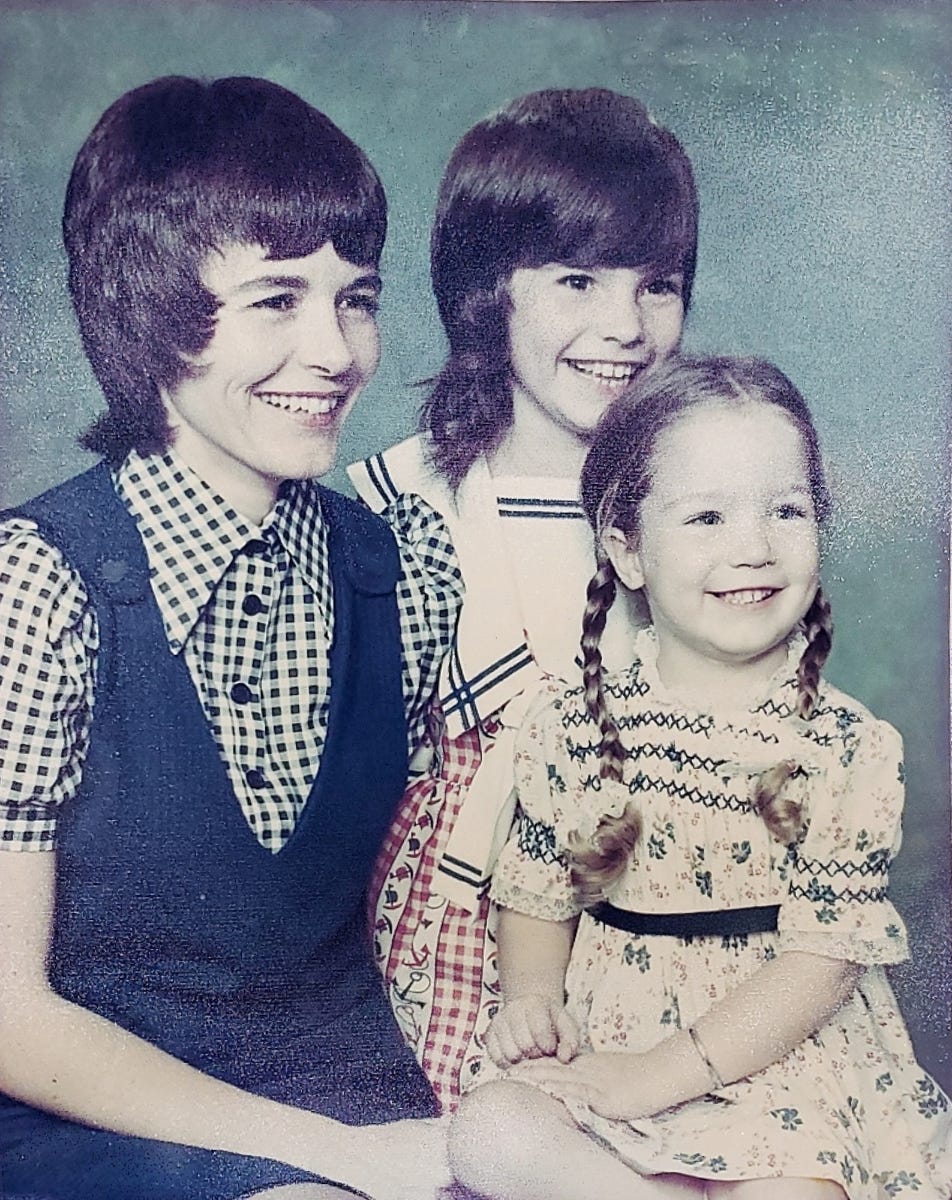

I spent my childhood in the warmth of her sunshine and in the shadow of her beauty. My blue eyes, auburn curls, and freckled cheeks were in direct contrast with her jet black hair that eventually turned snow white, her mocha eyes, and her perfect olive skin. She would tan in the summer while I often ended up sunburned and in vinegar baths. My sister, Carrie, resembled my mom, and I was my biological dad through and through. People called me “cute” when I was little, but I always wanted to be “stunning,” like my mom.

Suitor after suitor came through our apartment door. Some would bring gifts to Carrie and me, one promised to buy me a new basketball and all the peanut butter I could ever eat if I convinced Mom to marry him. One—the karate instructor who trained her all the way to her black belt—took us on a trip to Chicago in his slick Pontiac Trans Am, and I fancied myself a Hollywood star. One, when asking for Mom’s hand, said he was “ready to take on the load.” Mom, cool and collected, asked if “the load” was her or her children before she ended that relationship forever.

Mom had chosen my biological dad when she was young. He: the gorgeous, chiseled, gap-toothed football player with ocean eyes. She: the Indianapolis Home Show queen, with a jawline so sharp it could cut glass, and a grace and eloquence about her that rivaled a young Katharine Hepburn. Mom and Dad were dubbed “The Golden Couple.” It was a match seemingly made in heaven, but my dad couldn’t stay. He was a dreamer, a searcher, the life of the party, and the party was not at home with two small children.

So my single mom dated a lot when we were young. Men lined up for a chance to treat her to dinner. But she always said to Carrie and me, “If you don’t like him, I don’t, either. If anyone makes you feel off in any way, he’s gone. You two will always come first.” And that’s exactly how she lived.

Then came the day when she introduced us to a new love interest. Carrie, 19 at the time, was living her own life, but I, at 13, was still very much at home with Mom.

“I really like him,” Mom said before he arrived. “I think you will, too.”

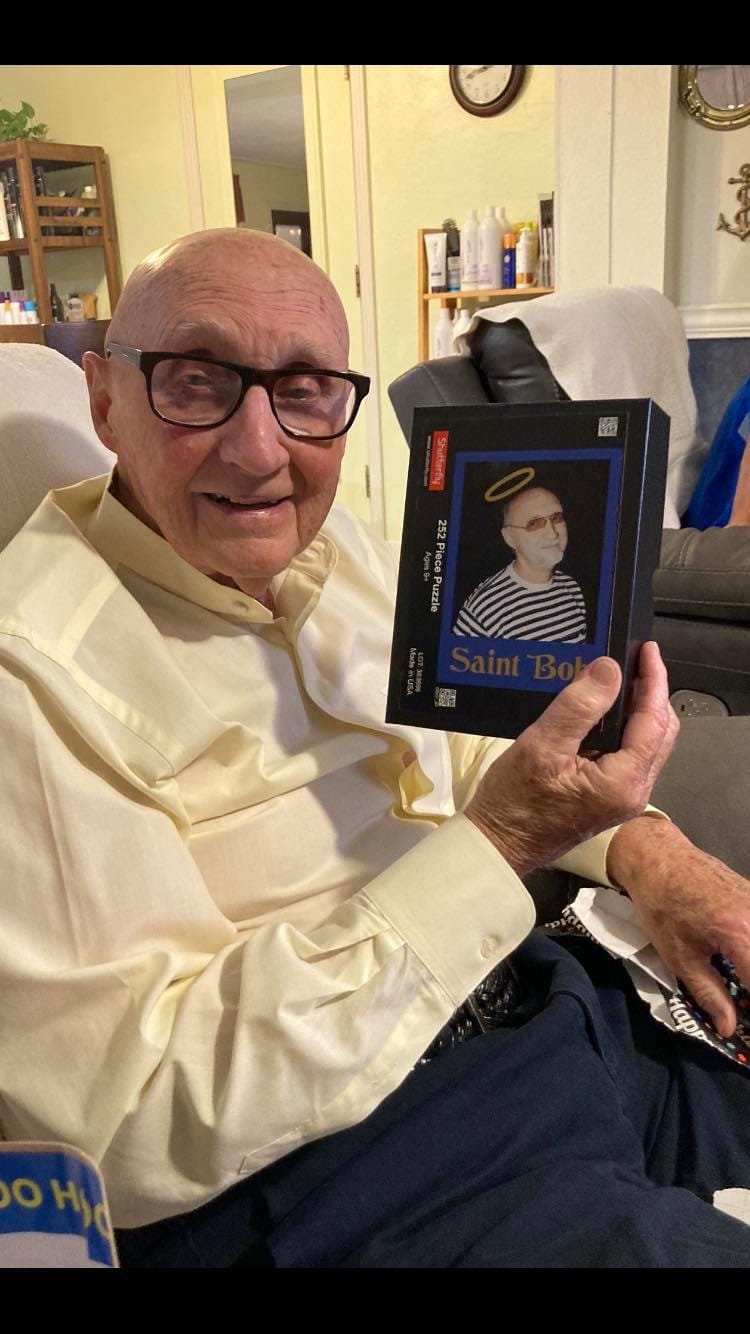

When I opened our door to greet Bob, I was taken aback. He was not like the other men Mom had dated. Balding and goateed, he was cute, but not drop-dead gorgeous like most of the men who had tried their best to woo her. But there was a gentle warmth and kindness about him that radiated from within. He was an avid sports fan and an athlete himself, so we instantly bonded over basketball. He instilled in me the importance of mastering both right-handed and left-handed layups, and he taught me the joy of racquetball, although I could never manage to beat him.

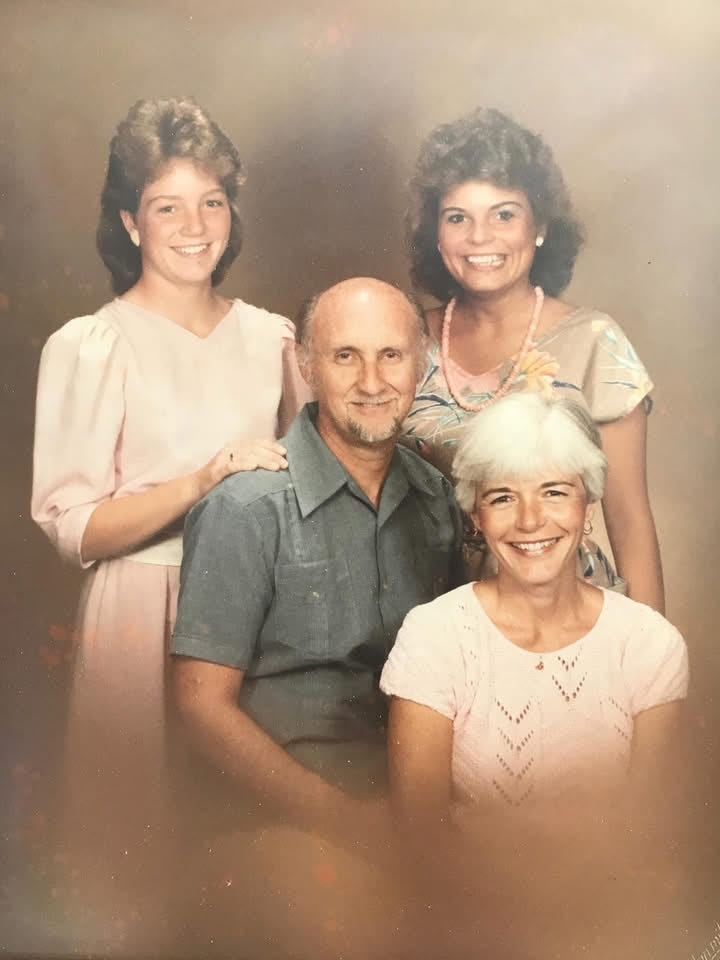

Mom and Bob married when I was 14 and Carrie was 20 in a small ceremony at a dear friend’s home, surrounded by loved ones. Carrie and I sang John Denver and Placido Domingo’s “Perhaps Love,” and we toasted our new family, made complete with a step-sister, Karla, and a step-brother, Kyle, who were both grown and out of the home. So, Mom, Bob, and I moved into a 3-bedroom ranch in Bowman Acres, and I started high school the following year.

As a 3-sport athlete in volleyball, basketball, and softball, my high school years were comprised primarily of school, practice, homework, sleep, rinse, and repeat. Bob drove me to before-school free-throw shooting practices and picked me up once my long school day was over. “Keep your feet off the dashboard, please, kiddo,” he’d request as I slumped in the front seat of his Oldsmobile. “Why?” I asked, snotty and petulant because I was 14. “Because I don’t want your shoes scratching it up,” he replied, calm and cool.

Every Sunday, Bob would pick his mother, Sarah, up from the nursing home, and the four of us would have lunch at MCL cafeteria. As Sarah’s health began failing, Bob would patiently spoon each bite into her mouth and wipe it clean when she was finished. I once asked Mom why she chose Bob out of all the suitors who’d wanted her hand. “It was a simple decision,” she said. “Because I witnessed the way he cared for his mom.”

I had always harbored a deep longing for my biological dad, a strong and insatiable yearning for him to come home and stay. And, of course, I took those deep-seated feelings of disappointment out on my new step-dad, arguing with him at every turn. I wasn’t particularly pleasant at 14 and 15, with hormones and angst raging through my system. I was angry at my biological dad, angry at the world, angry at my feelings of injustice and inequality. My cousins and friends had fathers who stayed. Why didn’t I?

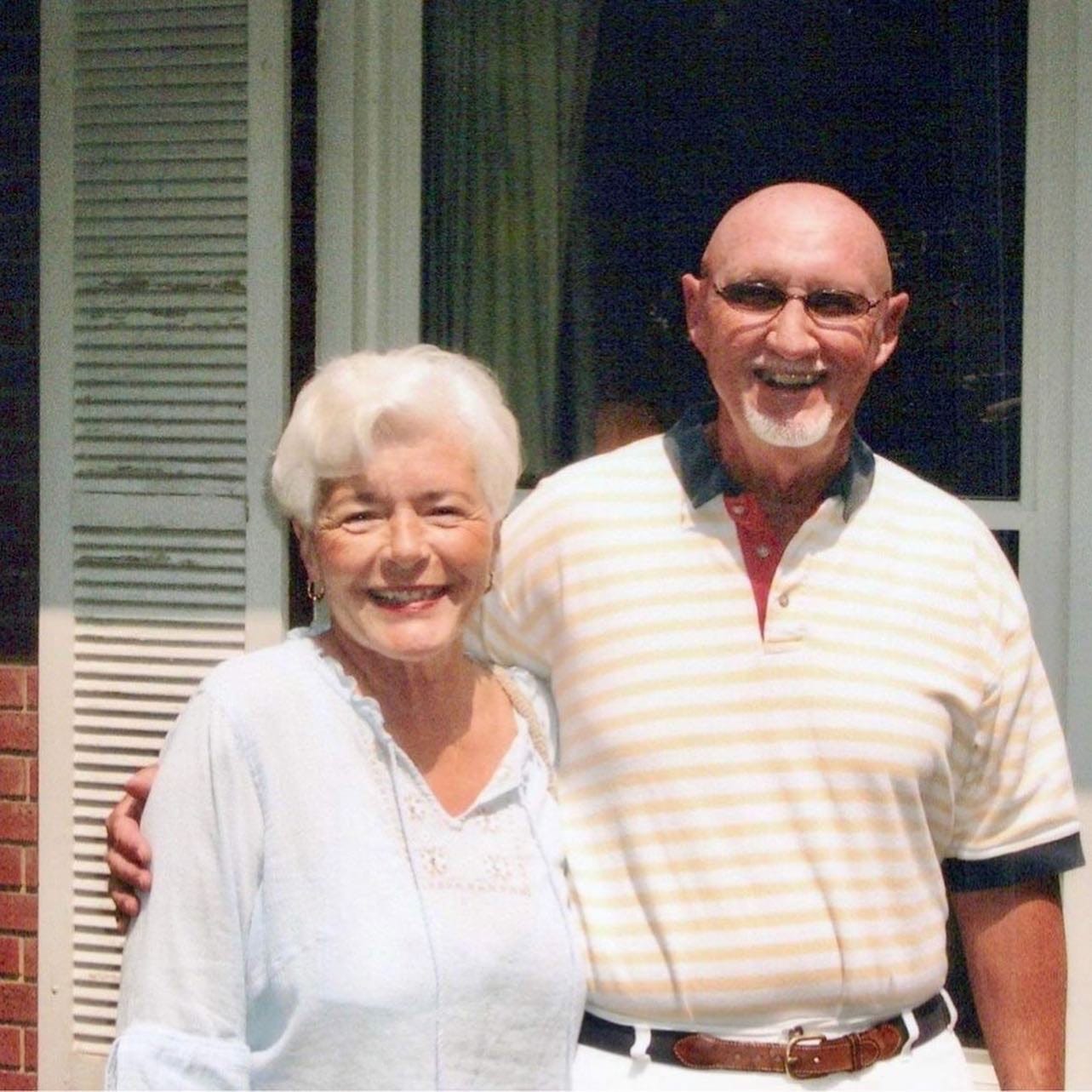

Throughout all my teenage upheaval, Bob remained steady and true. He adored my mom, and he never raised his voice at me. The two of them sat in the stands, side by side, at every game—both home and away. They hung out with my friends’ parents and went dancing at The Anchor Inn. They supported me, cheered me on, drove me to and from all my events, kept me outfitted in new high-tops and cleats. They were my biggest fans.

When I got married and began to have babies of my own, Mom and Bob were over the moon. One of the first words each of my kids spoke was “Bob”—it was simple to say, and they adored Grandpa Bob with every ounce of their little hearts. Mom couldn’t get enough of my kids, and Grandpa Bob spoiled them with Sweet Shop donuts, pre-work breakfasts in the Eli Lilly cafeteria, golf outings, and trips to the zoo. Mom and Bob sat in the stands and cheered my kids on in baseball, softball, basketball, and lacrosse, just as they’d done for me.

Then Mom got sick.

As Mom’s health began to fail due to MS, Bob’s focus shifted. They traveled less and stayed home on Mom’s “bad days.” Bob became Mom’s devoted caregiver—doing all the grocery shopping, paying bills, picking up prescriptions, cooking meals. Just as he’d cared for his own mom, he cared for my mom with patience, kindness, and unwavering love.

When my mom died and Bob’s Alzheimer’s began to progress, he moved to Florida to live with Kyle and Jeanna. During visits, he’d say, “It’s so nice to be here in Florida, but I sure wish that pretty, white-haired lady was here to share it with me.”

We lost our Bob in the early morning hours last Thursday. He died peacefully with Kyle, Jeanna, and his grandson, Kyle Junior, by his side. He was 88, and when he took his last breath, he left a legacy of love, devotion, kindness, strength, faith, and friendship in his wake.

He was the last of my family of origin to leave me as well. I lost my beloved mom in 2021, my only sister in 2022, my biological dad in 2024, and my sweet Bob in 2025. It is a strange and surreal feeling to be the only one left at age 55. I was in Greenfield a couple of weeks ago to say goodbye to my former mother-in-law, and it felt like a place I no longer knew. I drove by the old apartment building, by St. Michaels, by Greenfield Central High School, by our house on Bowman. And, of course, nothing had remained the same. Home is a place, but it is also a feeling. It is the people, the life, the love. My home has been irrevocably altered with the loss of Bob, and I am unmoored.

My four adult children have lives of their own. They are fiercely independent, which is exactly who I raised them to be. I encouraged their adventures, supported their dreams, cheered them on as they found their wings. But the downside of that particular brand of parenting is that they have flown far away. Three of them are in the Pacific Northwest, and although one remains physically close, he, too, is busy with his own life. It’s some real “Cat’s in the Cradle” stuff. I see my friends celebrating every special occasion with their grown children, their grandchildren, their parents. I am lucky to see my kids once a year. That’s not a complaint—it’s just a reality. My life is very different than many I know in that way. I am so proud of and happy for my kids. And I miss them desperately. Both things can be true at once. Both things are.

My hope is that—like my own memories of childhood—my children carry bedtime stories and bubble baths and trips to the Children’s Museum with them. I hope they remember the first time they swam in the ocean, the first roller coaster they rode, and the first time they saw a shooting star at the beach. I hope they are made of movie nights on the driveway and homemade birthday cakes and looking up into the bleachers to see me cheering for them. I hope these things reside just beneath the tough veneer of their skin so their hearts remain soft with the memory of my love for them. I hope no matter how far they travel or wherever they might live, they take what made them and they fortify themselves with it. I understand how it feels to be made of the best kinds of memories. I wish that for them, too. I hope that if they someday choose to have children, they will understand the depth of what I feel for them. And if they don’t have children, I still hope they know.

It is a strange place to exist in right now—that space between losing my family of origin and letting my kids fly. It is the space in which I find myself after coming out in 2016, after ending my marriage of 25 years, and rearranging life as I’d known it forever. I find myself—now more than ever—creating and nurturing chosen family. With like-minded friends within the queer community; with those who accept me for me—not necessarily for who they believed I once was.

And at the same time, I find my body failing in ways I could not have imagined at 55. I’ve had a total knee replacement, a complete hysterectomy, a CMC arthroplasty. I just had an MRI that declared I have severe degenerative disc disease in my lumbar spine and displacement of my right S1 nerve root. It is the reason I cannot walk very far or for very long. It is the reason my body aches with bone-deep pain for two days after I play two hours of pickleball. It is the reason I cannot stand in one place for more than a few minutes. I have always considered myself adventurous, active, athletic. Who am I if my spine no longer agrees? I watched my mom succumb to a wheelchair; I watched my sister limp her way to her death, dragging her neuropathic limbs along with her. I cannot allow myself the same. I simply cannot. And so, I am fighting every day to stay active, to stay limber, to eat foods with fewer than five ingredients, to avoid my beloved sweets as much as possible. This body is 50 pounds heavier than I’d like it to be. My spine concurs. But, of course, I cannot move like I once could, so I have to figure out another path. Fewer calories, laps in the pool, things that are somewhat foreign to me. I’d rather run for four hours to burn the calories, but my body tells me that’s no longer an option.

Everything changes, doesn’t it? And the best we can do is change with it.

I have had immeasurable loss in the past decade of my life. From 46 to 55, most everything in my universe changed. I am no longer the person I once believed myself to be. And yet, in the most fundamental ways, I still am. My family has changed, my identity, my geography, my body, my relationships, my belief systems. But I am here, holding on to hope, writing it all, making some sense of what no longer seems to make any sense at all.

The night sweet Bob was making his passage into whatever comes next, there was a bright “fingernail” moon in the dark evening sky. Fingernail moons were my mom’s favorite. I have one tattooed on my arm, next to the text, “Love Always, Mom” in my mother’s handwriting. I imagine Mom sent that moon just for Bob, to guide him back to her, where they could jitterbug together forever in the stardust.

Because everything changes, but yet, what’s true and real will always remain the same. Godspeed, Bob. Please hug my family for me when you find them in the cosmos.

I’m not crying, you’re crying. What a gorgeous tribute to Bob, and your original family.

Thank you for this beautiful and profound essay. Bob was most definitely a gift to you and your family. It is profound when we become adult orphans and our family of origin is gone, and you’ve offered some beautiful philosophical gems for readers to cherish as they move through their lives—and also spoken for those of us who’ve already walked some of those same paths. You’ve touched my heart. Thank you.